This article explains why PlanToIt exists as a company. It reflects the business reality that led to building a new approach to forecasting and inventory decisions in food operations.

I did not start PlanToIt because the world needed another planning platform. When I began working in this space, food and beverage companies were already surrounded by systems promising accuracy, optimization, and control. Many of those systems were well designed, well funded, and widely deployed.

What stood out was not a lack of technology. The same operational failures kept repeating in organizations that were considered disciplined and experienced. Products went out of stock in some locations while excess inventory accumulated in others. New launches that looked solid during planning became confusing once they reached stores and kitchens.

Teams responded by working harder and adding more process, but the results did not change. They still found themselves reacting after problems had already taken shape. Over time, it became clear that these outcomes were not coincidences or isolated failures, but signals of a deeper issue in how planning was structured.

Why This Is Structural, Not Execution

The same failures appeared across different companies, regions, and operating models, regardless of the people or systems involved. It is how teams approach the problem and what the foundations are that they base their planning on. That is why when the same failures occur across different organizations and technology stacks, execution alone cannot explain the outcome.

In day-to-day food operations, inventory expires quickly, ordering decisions are short, and substitutions happen as part of normal execution. That is the reality, and systems need to reflect this. It’s what happens when customer behavior shifts mid-cycle and the sales data is too slow to catch it. These conditions shape how teams actually make decisions, whether or not systems are designed for them.

This isn’t a theoretical problem. Customer behavior often pivots mid-cycle, long before a sales report flags the change. These real-world pressures dictate the decisions teams make, even when the software ignores them.

When planning systems are designed to operate far away from these realities, they can appear stable and reliable while failing precisely when timing and precision matter most.

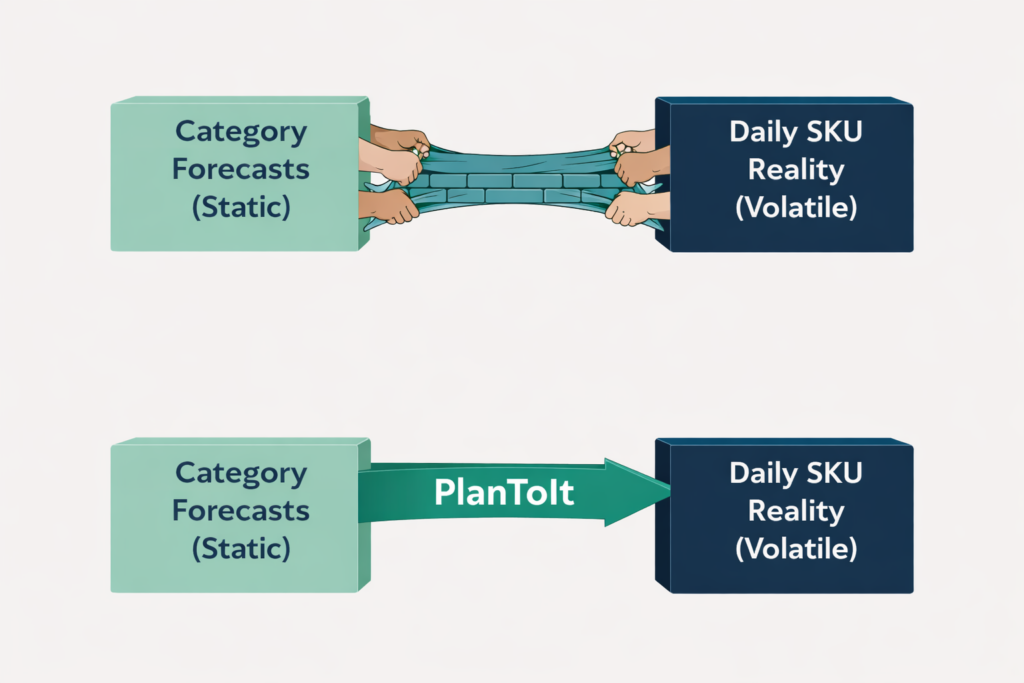

The Gap Between Systems and Operations

We live in a world where everything must be faster than it was a decade ago. Identifying problems, gaps, or changes, and the ability to act on them. The story operations and supply chain teams keep telling themselves is that this is how it works, and no one or no software product can solve this problem, but that is not true anymore, especially with AI capabilities.

What I observed over and over in every organization I worked with, including colleagues sharing the same thing, was a growing gap between what systems reported and what teams experienced on the ground. Anyone who has spent enough time in logistics has seen a similar pattern. Forecasts look acceptable, reports appear balanced, yet shelves tell a very different story as waste and shortages quietly build up.

As usual, demand planners fixed it all manually, relying on their experience and judgment to bridge gaps the system could not identify, often with little time to recover once decisions were locked in. Manual fixing was the only solution five or ten years ago, but when companies drastically lay off employees to reduce work teams because they rely on technology, employees reach a limit to what they can fix manually in an eight-hour workday.

It is acceptable that some work will be adjusted manually, but it is unreasonable to expect most work to be done manually to bridge gaps the current system does not address, while companies keep paying for licenses and maintenance.

In many cases, the systems were not broken. They were doing exactly what they were designed to do. They were optimized for aggregation, smoothing, and long-range visibility. Those design choices make sense from a software and reporting perspective.

The cost of those choices, however, is paid downstream in operations, where there is very little room to recover once decisions are locked in.

Why We Did Not Add Another Layer

At some point, it became clear that adding more intelligence or automation on top of the same architecture would not fix the underlying problem. Improving accuracy within the same orientation only makes the mismatch harder to detect, because cleaner forecasts encourage teams to trust the system longer, even when reality starts to drift.

The issue was not forecasting sophistication. We needed to move the forecast closer to the actual work.

Why Responsibility Became the Focus

I founded PlanToIt to change where responsibility lives. As long as systems operate far from execution, people will continue to absorb risk manually.

PlanToIt exists to return responsibility to the system, inside the window where decisions still matter.

What We Built Instead

We did not start by asking how to improve forecasting. We started by asking where food decisions are actually made and what conditions surround those decisions. From that perspective, the design choices became straightforward.

Planning at the SKU level is the default in everything we do. It is the baseline because that is how food operations work in the real world. It is not wishful thinking. It is what affects grocery shopping and people’s restaurant choices.

Short-term forecasting is not a limitation. You just need to know how to do it right, as it requires knowledge and experience. Forecasting by SKU reflects ordering cycles, shelf life, and supply variability. Volatility is not treated as noise to be smoothed away, but as information that needs to remain visible early enough to act on.

PlanToIt was built around these realities from the beginning. It was not designed as an add-on to existing planning logic, and it was not meant to explain outcomes after the fact. It was designed to support decisions while they are still changeable.

That goal shaped our system and product architecture over time. If we want to help companies win in today’s reality, we must provide them with the most accurate, up-to-date information as quickly as possible to enable them to make informed decisions about how the world behaves.

Why Timing Is the Real Constraint

Do teams need explanations once outcomes are already irreversible? That only increases the flames of the fire and does not solve the problems, or at least gives them a hint on what to do. They need support earlier, at the moment hesitation appears, and there is still time to intervene.

PlanToIt exists to take responsibility for that gap, align planning systems with how food businesses actually operate, and give teams visibility and confidence within the window.

For a technical explanation of how PlanToIt was designed to operate differently at the system level, see the CTO perspective published here.